This blog post summarizes our paper entitled Testing the Impact of Prey Presentation Method on the Feeding Kinematics of Terrestrial and Aquatic Ambystomatidae published in Journal of experimental Zoology – Part A

Standardizing prey capture records is a tricky task!

Studying feeding kinematics of salamanders and newts requires the collection of numerous high-speed- prey-capture recordings across multiple individuals and species. We often work under tight time constraints, sometimes in laboratories abroad, with several researchers collecting data simultaneously. Moreover, animals must be fed to their usual feeding routine, otherwise, they may refuse to eat. As a result, small differences in the feeding protocol can occur depending on who collects the data and which animal is being filmed.

This led us to wonder whether holding prey with tweezers, instead of letting it on the substrate, could affect salamanders’ feeding movements. Because salamanders use different feeding strategies depending on whether they live in water or on land, we tested this question in two types of feeders:

- Five young Mexican axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum), which capture prey using suction feeding (see the video below or our previous blog post for details on how suction feeding works in axolotls).

- Three adult tiger salamanders (Ambystoma tigrinum) and two adult barred tiger salamanders (Ambystoma mavortium), which typically capture prey using tongue prehension (see video below) *.

* We treated tiger and barred tiger salamanders as a single group in our analyses because they are cryptic species: they share the same morphology but differ genetically.

Axolotls were sensitive to how prey was presented!

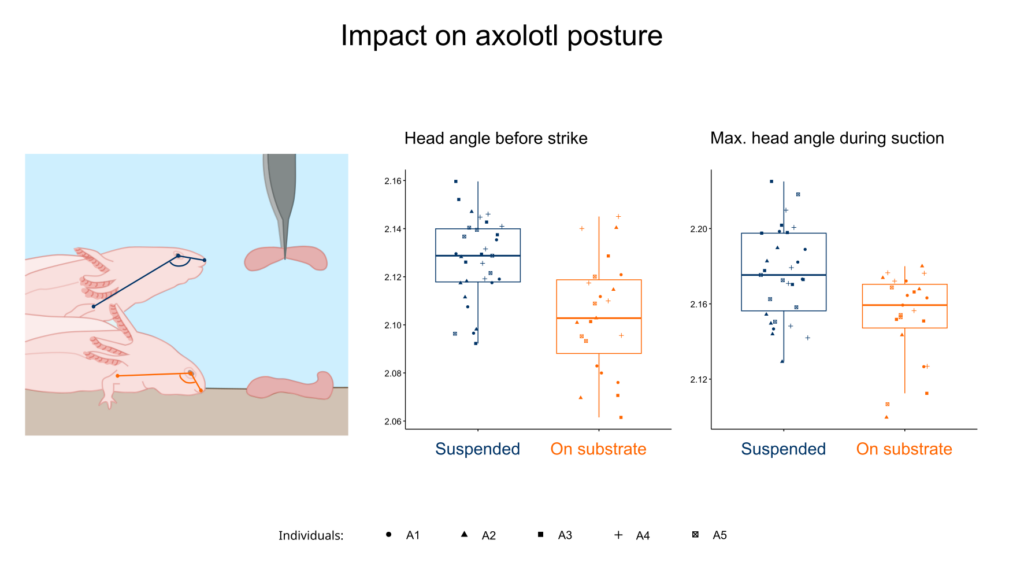

Axolotls adapted their posture…

The head angle before strike and the maximum head angle during suction was higher when prey was held with tweezer for the simple reason that prey was suspended above the axolotl, unlike when it rested on the substrate.

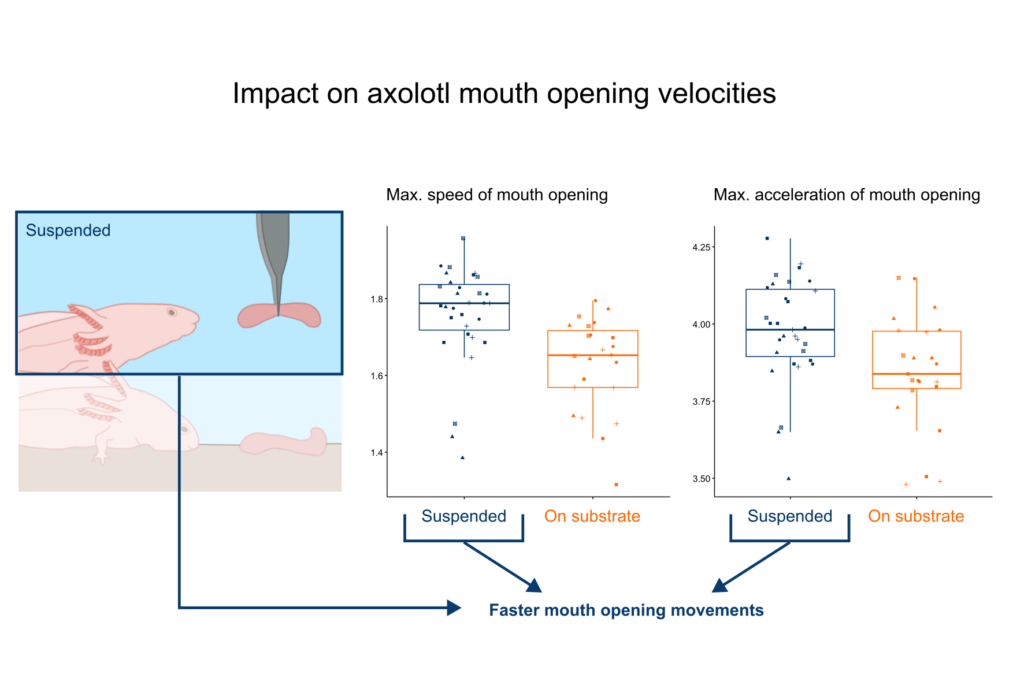

… As well as the way they opened their mouth:

When prey was held with tweezers, axolotls opened their mouth faster. This likely helped them reach peak flow velocity more quickly, a known way to increase the suction force.

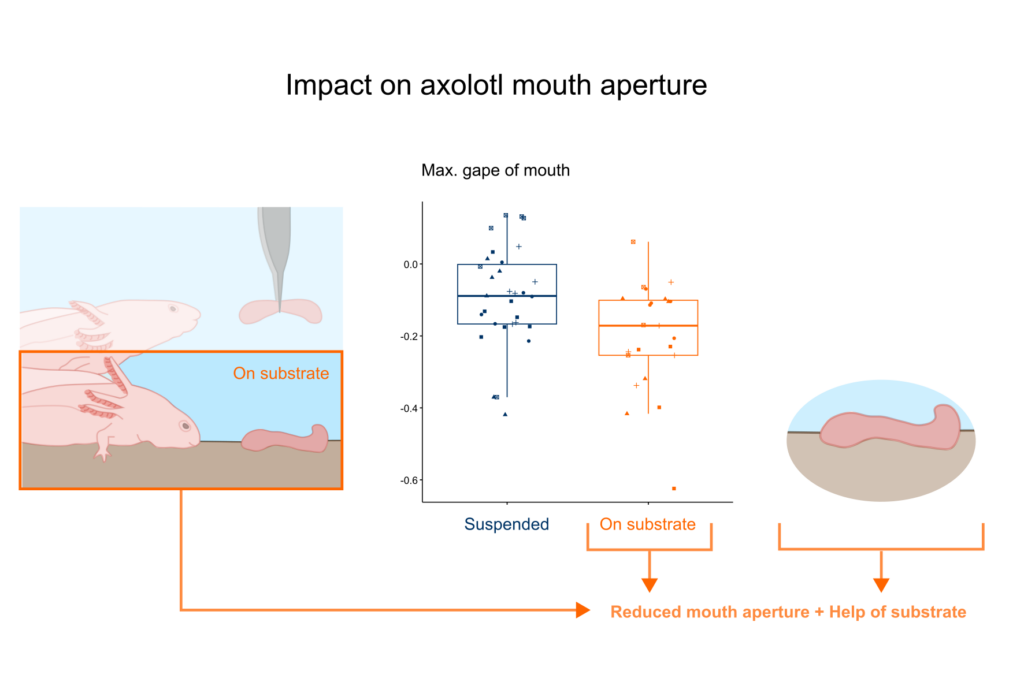

When prey was on the substrate, they opened their mouth less wide, which is another way to increase suction force. However, compared to opening the mouth quickly, reducing mouth aperture generate a force which drops off more quickly with distance. But they likely compensated using the substrate. Thanks to the substrate the space becomes relatively 2-dimensional which permits to concentrate the flow and double the distance from which prey can be successfully captured.

Barred tiger and tiger salamanders were not sensitive to the way prey was presented

Terrestrial salamanders did not adapt their posture…

The head angle was not impacted by how prey was presented. Moreover, we noticed that unlike axolotls, which always positioned their snouts near or touching the prey, tiger and barred tiger salamanders did not move closer when the prey was farther away. Instead, they lunged or jumped suddenly toward it.

…nor their feeding kinematics

There were no significant changes in feeding kinematics depending on how prey was presented. We only observed that jaw prehension occurred more often when prey was held with tweezers (12 times versus only once when prey was on the substrate). Interestingly, this behavior always followed a failed tongue prehension attempt.

Feedforward, feedback, and why medium matters more than the way prey is presented

Suction feeding requires extremely rapid movements, so axolotls must anticipate their strike based on the situation, this is a feedforward mechanism. This explains why prey presentation affects their feeding kinematics.

Terrestrial feeding is slower and less constrained. Salamanders rely on feedback from their tongue pad: if the prey isn’t captured during retraction, they can switch to jaw prehension mode. This feedback mechanism likely explains why prey presentation has little effect on their feeding movements.

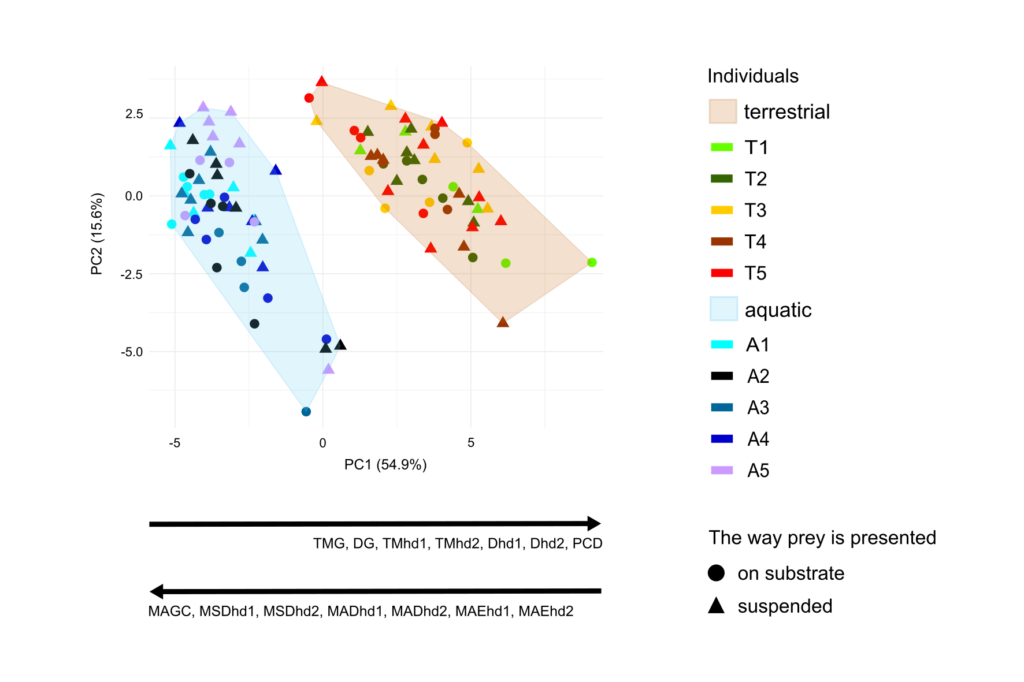

At the end, when aquatic and terrestrial data sets are combined, the effect of the way prey is presented is overridden by the larger differences between feeding in water and on land (see PCA). This suggests that the importance of accounting for prey presentation depends on the context and the level of analysis.

So, do salamanders change their table manners when food is served with tweezers?

Well… axolotls apparently do! They adjust their posture, tweak their suction, and optimize their hydrodynamics like tiny aquatic engineers. Tiger salamanders, on the other hand, couldn’t care less about fine dining etiquette: if the tongue fails, they just go full “plan B” and bite.

In short, for salamanders, it’s not about the cutlery, it’s about the medium. Water demands strategy; land allows improvisation.

And if there’s one takeaway from this study, it’s this: when you’re filming feeding kinematics, never underestimate the power of tweezers… they might just turn dinner into biomechanics.

For a more detailed version of our study, read our paper