Take a moment to consider your jaw – that bone that gives you your characteristic chin and that maybe gives you a toothache every once in a while. Your lower jaw, also called the mandible or dentary, is a single bone that has 14-16 teeth for biting and chewing your food, a joint back near your ear that allows you to move and rotate your jaw in several directions, anchor points for your tongue so you can speak, and attachment sites for the muscles that power biting and chewing. Think of these like different “modules” of your lower jaw.

All of these different functions (modules) give our lower jaw and the lower jaw of all other vertebrates different anatomical regions (like different regions of a country): tooth anchoring sites, muscle attachment sites, articulation sites with other bones, etc. As the lower jaw changes size and shape over the course of evolution, do these different regions of the lower jaw evolve together or separately? That is, do all these regions of the lower jaw change together or do different regions “do their own thing” and act semi-autonomously (to continue the geographic metaphor)? From previous research, we know that the lower jaw in mammals (like us) generally evolves in the second manner (different regions evolving somewhat independently). But is the same true for amphibians such as frogs and salamanders?

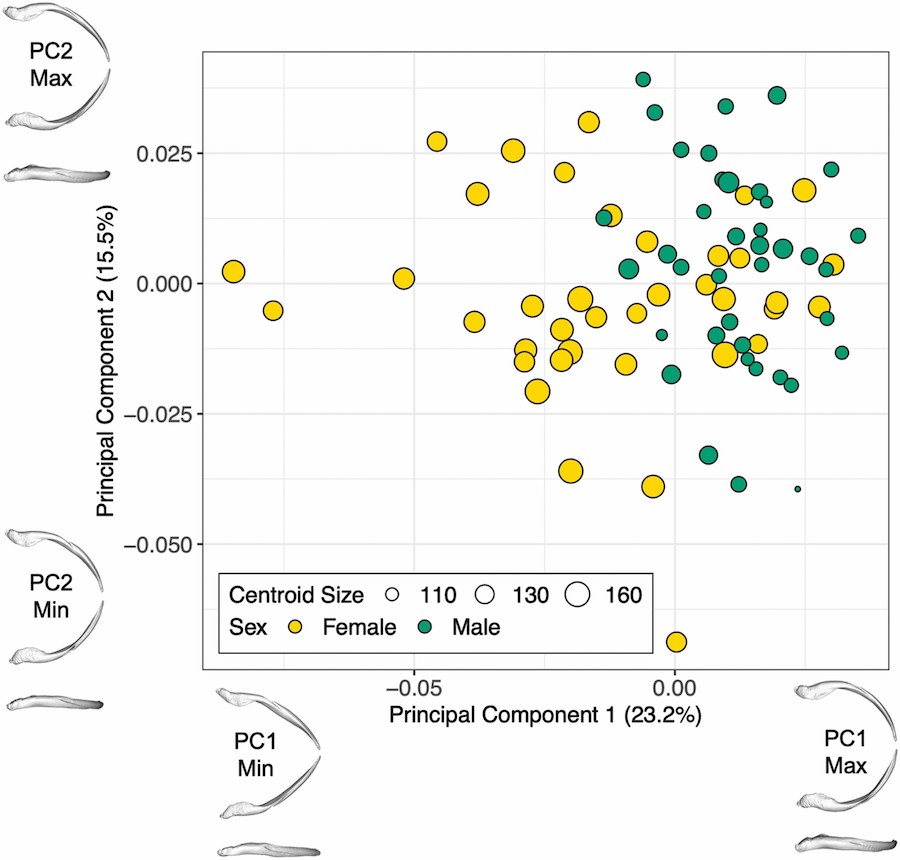

In our latest paper, out today in the journal Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, we answer the question of whether the lower jaw in amphibians evolves as a single unit or, like mammals, evolves with different regions evolving in different ways. Using CT scans from more than 100 lower jaws of African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis) and fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra gigliolii), we mapped out how lower jaw shape varies within each of these species. Using these maps of variation, we then used statistical models to evaluate whether this variation fits the single-unit or regional pattern.

We found that amphibian lower jaws, like those of mammals, fit the regional pattern with different modules of the lower jaw evolving with some independence from one another. We found that in amphibians, the functions of these modules best explained this patchwork pattern: parts of the lower jaw with the same function evolved together and parts with different functions, evolved separately. These results show that this region-by-region evolution of the lower jaw is likely widespread across many groups of vertebrates, including mammals, birds, and reptiles, and that what we think of as a single bone can be the result of a patchwork of parts, each evolving according to its particular function.

Stevens, Maddison, Anne-Claire Fabre, and Ryan N. Felice. “Lower jaw modularity in the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) and fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra gigliolii).” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (2023): blad087. DOI: 10.1093/biolinnean/blad087.